Introductory Comparison of the Five Tibetan Traditions of Buddhism and Bon

Alexander Berzin

Berlin, Germany, January 10, 2000

supplemented with excerpts from a lecture on the same topic

Munich, Germany, January 30, 1995

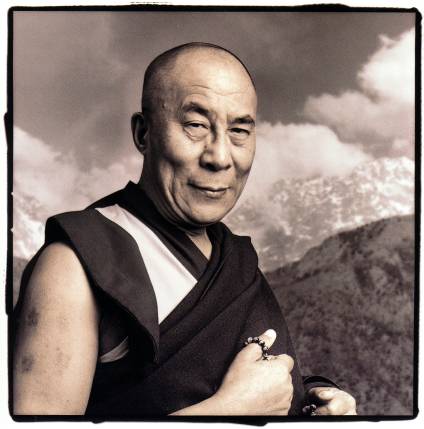

Bon as the Fifth Tradition of Tibet

Most people speak of Tibet as having four traditions: Nyingma,Kagyu, Sakya, and Gelug, with Gelug being the reformed continuation of the earlier Kadam tradition. At the nonsectarian conference of tulkus (incarnate lamas) and abbots that His Holiness the Dalai Lama convened in Sarnath, India, in December 1988, however, His Holiness emphasized the importance of adding the pre-Buddhist Tibetan tradition of Bon to the four and always speaking of the five Tibetan traditions. He explained that whether or not we consider Bon a Buddhist tradition is not the important issue. The form of Bon that has developed since the eleventh century of the Common Era shares enough in common with the four Tibetan Buddhist traditions for us to consider all five as a unit.

Hierarchy and Decentralization

Before we discuss the similarities and differences among the five Tibetan traditions, we need to remember that none of the Tibetan systems forms an organized church like, for example, the Catholic Church. None of them is centrally organized in this manner. Heads of the traditions, abbots, and so on are mainlyresponsible for giving monastic ordination and for passing on lineages of oral transmissions and tantric empowerments(initiations). Their main concern is not with administration. Hierarchy mostly affects where people sit in the large ritual ceremonies (pujas); how many cushions they sit on; the order in which they are served tea; and so on. For various geographic and cultural reasons, the Tibetan people tend to be extremely independent and each monastery tends to follow its own ways. The remoteness of the monasteries, huge distances between them, and difficulties in travel and communication have reinforced the tendency toward decentralization.

Common Features

The five Tibetan traditions share many common features, perhaps as much as eighty percent or more. Their histories reveal that the lineages do not exist as separate monoliths isolated within concrete barriers, without any contact with each other. The traditions have congealed into five from their founding masters having gathered and combined within themselves various lines of transmission, mostly from India. By convention, their followers have called each of their syntheses "a lineage," but many of the same lines of transmission form part of the blends of other traditions as well.

Lay and Monastic Traditions

The first thing the five share in common is having both lay and monastic traditions. Their lay traditions include married yogisand yoginis engaged in intensive tantric meditation practice and ordinary laypeople whose Dharma practice entails mostly recitingmantras, making offerings at temples and at home, and circumambulating sacred monuments. The monastic traditions of all five have the full and novice monk ordination and the novice nun ordination. The full nun ordination never came to Tibet. People normally join the monasteries and nunneries around the age of eight. Monastic architecture and décor are mostly the same in all traditions.

The four Buddhist schools share the same set of monastic vowsfrom India, Mulasarvastivada. Bon has a slightly different set of vows, but most of them are the same as the Buddhist. A prominent difference is that Bonpo monastics take a vow to be vegetarian. The monastics of all traditions shave their heads; remain celibate; and wear the same maroon sleeveless habit, with a skirt and a shawl. Bon monastics merely substitute blue for yellow in the central panels of the vest.

Sutra Study

All Tibetan traditions follow a path that combines sutra andtantra study with ritual and meditation practice. The monastics memorize a vast number of scholarly and ritual texts as children and study by means of heated debate. The sutra topics studied are the same for both Buddhists and Bonpos. They includeprajnaparamita (far-reaching discrimination, the perfection of wisdom) concerning the stages of the path, madhyamaka (the middle way) concerning the correct view of reality (voidness),pramana (valid ways of knowing) concerning perception and logic, and abhidharma (special topics of knowledge) concerning metaphysics. The Tibetan textbooks for each topic differ slightly in their interpretations not only among the five traditions, but also even among the monasteries within each tradition. Such differences make for more interesting debates. At the conclusion of a lengthy course of study, all five traditions grant a degree, either Geshe or Khenpo.

The four Tibetan Buddhist schools all study the four traditions of Indian Buddhist philosophical tenets - Vaibhashika, Sautrantika,Chittamatra, and Madhyamaka. Although they explain them slightly differently, each accepts Madhyamaka as presenting the most sophisticated and precise position. The four also study the same Indian classics by Maitreya, Asanga, Nagarjuna, Chandrakirti, Shantideva, and so on. Again, each school has its own spectrum of Tibetan commentaries, all of which differ slightly from each other.

Tantra Study and Practice

The study and practice of tantra spans all four or six classes of tantra, depending on the classification scheme. The four Buddhist traditions practice many of the same Buddha-figures (deities,yidams), such as Avalokiteshvara, Tara, Manjushri, Chakrasamvara (Heruka), and Vajrayogini (Vajradakini). Hardly any Buddha-figure practice is the exclusive domain of one tradition alone. Gelugpas also practice Hevajra, the main Sakya figure, and Shangpa Kagyupas practice Vajrabhairava (Yamantaka), the main Gelug figure. The Buddha-figures in Bon have similar attributes to the ones in Buddhism - for example, figures embodying compassion or wisdom - only different names.

Meditation

Meditation in all five Tibetan traditions entails undertaking lengthy retreats, often for three years and three phases of the moon. Retreats are preceded by intensive preliminary practices, requiring hundreds of thousands of prostrations, mantra repetitions, and so on. The number of preliminaries, the manner of doing them, and the structure of the three-year retreat differ slightly from one school to another. Yet, basically, everyone practices the same.

Ritual

Ritual practice is also very similar in all five. They all offer water bowls, butter lamps, and incense; sit in the same cross-legged manner; use vajras, bells, and damaru hand-drums; play the same types of horns, cymbals, and drums; chant in loud voices; offer and taste consecrated meat and alcohol during special ceremonies (tsog); and serve butter tea during all ritual assemblies. Following the originally Bon customs, they all offertormas (sculpted cones of barley flour mixed with butter); enlist local spirits for protection; dispel harmful spirits with elaborate rituals; make butter sculptures on special occasions; and hang colorful prayer flags. They all house relics of great masters instupa monuments and circumambulate them - Buddhists clockwise, Bonpos counterclockwise. Even their styles of religious art are extremely similar. The proportions of the figures in paintings and statues always follow the same set guidelines.

Tulku System of Reincarnate Lamas

Each of the five Tibetan traditions also has the tulku system. Tulkus are lines of reincarnate lamas, great practitioners who direct their rebirths. When they pass away, usually in a special type of death-juncture meditation, their disciples use special means to look for and locate their reincarnations among young children, after an appropriate time has passed. The disciples return the young reincarnations to their former households and train them with the best teachers. Monastics and laypeople treat the tulkus of all five traditions with the highest respect. They often consult tulkus and other great masters for a mo(prognostication) about important matters in their lives, usually made by tossing three dice while invoking one or another Buddha-figure.

Although all Tibetan traditions include training in textual study, debate, ritual, and meditation, the emphasis varies from monastery to monastery even within the same Tibetan school and from individual to individual even within the same monastery. Moreover, except for the high lamas and the elderly or sick, the monks and nuns take turns in doing the menial laborrequired to support the monasteries and nunneries, such as cleaning the assembly halls, arranging offerings, fetching water and fuel, cooking, and serving tea. Even if certain monks or nuns primarily study, debate, teach, or meditate; still, engaging in communal prayer, chanting, and ritual takes up a significant portion of everyone's day and night. To say that Gelug and Sakya emphasize study, while Kagyu and Nyingma stress meditation is a superficial generalization.

Mixed Lineages

Many lineages of teachings mix and cross among the five Tibetan traditions. The lineage of The Guhyasamaja Tantra, for example, passed through the translator Marpa to both the Kagyu and the Gelug schools. Although the mahamudra (great seal) teachings concerning the nature of mind are usually associated with the Kagyu lines, the Sakya and Gelug schools also transmit lineages of them. Dzogchen (the great completeness) is another system of meditation on the nature of the mind. Although usually associated with the Nyingma tradition, it is also prominent in theKarma Kagyu school from the time of the Third Karmapa and in the Drugpa Kagyu and Bon traditions. The Fifth Dalai Lama was a great master of not only Gelug, but also of dzogchen and Sakya, and wrote many texts on each. We need to be open-minded to see that the Tibetan schools are not mutually exclusive. Many Kagyu monasteries perform Guru Rinpoche pujas, for example, although they are not Nyingma.

Differences

Usage of Technical Terms

What are the major differences, then, among the five Tibetan traditions? One of the main ones concerns the usage of technical terms. Bon discusses most of the same things as Buddhism does, but uses different words or names for many of them. Even within the four Buddhist traditions, various schools use the same technical terms with different definitions. This is actually a great problem in trying to understand Tibetan Buddhism in general. Even within the same tradition, different authors define the same terms differently; and even the same author sometimes defines the same terms differently in his various works. Unless we know the exact definitions that the authors are using for their technical terms, we can become extremely confused. Let me give a few examples.

Gelugpas say that mind, meaning awareness of objects, is impermanent, while Kagyupas and Nyingmapas assert it is permanent. The two positions seem to be contradictory and mutually exclusive; but, actually, they are not. By "impermanent," Gelugpas mean that awareness of objects changes from moment to moment, in the sense that the objects one is aware of change each moment. By "permanent," Kagyupas and Nyingmapas mean that awareness of objects continues forever; its basic nature remains unaffected by anything and thus never changes. Each side would agree with the other, but because of their using the terms with different meanings, it looks as if they completely clash. Kagyupas and Nyingmapas would certainly say that an individual's awareness of objects perceives or knows different objects each moment; while Gelugpas would certainly agree that individual minds are continuums of awareness of objects with no beginning and no end.

Another example is the word "dependent arising." Gelugpas say that everything exists in terms of dependent arising, meaning that things exist as "this" or "that" dependently on words andconcepts being able to validly label them as "this" or "that." Knowable phenomena are what the words and concepts for them refer to. Nothing exists on the side of knowable phenomena that by its own power gives them their existence and identities. Thus, for Gelugpas, existence in terms of dependent arising is equivalent to voidness: the total absence of impossible ways of existing.

Kagyupas, on the other hand, say that the ultimate is beyond dependent arising. It sounds as if they are asserting that the ultimate has independent existence established by its own power, not just dependently arising existence. That is not the case. Kagyupas, here, are using "dependent arising" in terms of thetwelve links of dependent arising. The ultimate or deepest true phenomenon is beyond dependent arising in the sense that it does not arise dependently from unawareness of reality (ignorance). Gelugpas would also accept that assertion. They are just using the term "dependent arising" with a different definition. Many of the discrepancies in the assertions of the Tibetan schools arise from such differences in the definitions of critical terms. This is one of the major sources of confusion and misunderstanding.

Viewpoint of Explanation

Another difference among the Tibetan traditions is the viewpoint from which they explain phenomena. According to the Rimey (nonsectarian movement) master Jamyang-kyentse-wangpo, Gelugpas explain from the point of view of the basis, namely from the point of view of ordinary beings, non-Buddhas. Sakyapasexplain from the point of view of the path, namely from the point of view of those who are extremely advanced on the path to enlightenment. Kagyupas and Nyingmapas explain from the point of view of the result, namely from a Buddha's viewpoint. As this difference is quite profound and complicated to understand, let me just indicate a starting point for exploring the issue.

From the basis point of view, one can only focus on voidness orappearance one at a time. Thus, Gelugpas explain even an arya's meditation on voidness from this point of view. An arya is a highly realized being with straightforward, nonconceptual perception of voidness. Kagyupas and Nyingmapas emphasize the inseparability of the two truths, voidness and appearance. From a Buddha's viewpoint, one cannot possibly talk about just voidness or just appearance. Thus, they speak from the point of view of everything being complete and perfect already. The Bon presentation of dzogchen accords with this manner of explanation. An example of the Sakya presentation from the point of view of the path is the assertion that the clear-light mind (the subtlest awareness of each individual being) is blissful. If that were true on the basis level, then the clear-light mind manifest at death would be blissful, which it is not. On the path, however, one makes the clear-light mind into a blissful mind. Thus, when Sakyapas speak of the clear-light mind as blissful, this is from the point of view of the path.

Type of Practitioner Emphasized

Another difference arises from the fact that there are two types of practitioners: those who travel gradually in steps and those for whom everything happens all at once. Gelugpas and Sakyapas speak mostly from the point of view of those who develop in stages; Kagyupas, Nyingmapas, and Bonpos, especially in their presentations of the highest class of tantra, often speak from the point of view of those for whom everything happens all at once. Although the resulting explanations may give the appearance that each side asserts only one mode of travel along the path, it is just a matter of which one they emphasize in their explanations.

Approach to Meditation on Voidness in Highest Tantra

As mentioned already, all the Tibetan schools accept Madhyamaka as the deepest teaching, but their ways of understanding and explaining the different Indian Buddhist systems of philosophical tenets differ slightly. The difference comes out most strongly in the ways in which they understand and practice Madhyamaka in highest tantra. As this is also a very complex and profound point, let us try here just to get an initial understanding.

Highest tantra practice leads to gaining straightforward nonconceptual perception of voidness with the subtlest clear-light mind. Thus, two components are necessary: clear-light awareness and correct perception of voidness. Which one receives the emphasis in meditation? With the "self-voidness" approach, the emphasis in meditation is on voidness as the object perceived by clear-light awareness. Self-voidness means the total absence of self-existent natures giving phenomena their identities. All phenomena are devoid of existing in this impossible way. Gelugpas, most Sakyapas, and Drigung Kagyupas emphasize this approach; although their explanations differ slightly concerning the impossible ways that phenomena are devoid of existing in.

The second approach is to emphasize meditation on clear-lightmind itself, which is devoid of all grosser levels of mind or awareness. In this context, clear-light awareness receives the name "other-voidness"; it is devoid of all other grosser levels of mind. Other-voidness is the main approach of the Karma, Drugpa, and Shangpa Kagyupas, the Nyingmapas, and a portion of the Sakyapas. Each, of course, has a slightly different way of explaining and meditating. One of the major areas of difference, then, among the Tibetan schools is how they define self-voidness and other-voidness; whether they accept one, the other, or both; and what they emphasize in meditation to gain clear-light awareness of voidness.

Regardless of this difference concerning self-voidness and other-voidness, all Tibetan schools teach methods for accessing clear-light awareness or, in the dzogchen systems, the equivalent:rigpa, pure awareness. Here, another major difference appears. Non-dzogchen Kagyupas, Sakyapas, and Gelugpas teach dissolving the grosser levels of mind or awareness in stages in order to access clear-light mind. The dissolution is accomplishedeither by working with the subtle energy-channels, winds, chakras, and so on, or by generating progressively more blissful states of awareness within the subtle energy-system of the body. Nyingmapas, Bonpos, and practitioners of Kagyupa lineages of dzogchen try to recognize and thereby access rigpa underlying the grosser levels of awareness, without actually having first to dissolve the grosser levels. Nevertheless, because earlier in their training they engaged in practices with the energy-channels, winds, and chakras, they experience that the grosser levels of their awareness automatically dissolve without conscious further effort when they finally recognize and access rigpa.

Whether Voidness Can Be Indicated by Words

Yet, another difference arises concerning whether voidness can be indicated by words and concepts or whether it is beyond both of them. This issue parallels a difference in cognition theory. Gelugpas explain that with nonconceptual sensory cognition, for example seeing, we perceive not only shapes and colors, but also objects such as a vase. Sakyapas, Kagyupas, and Nyingmapas assert that nonconceptual visual cognition perceives only shapes and colors. Perceiving the shapes and colors as objects such a vase occurs with conceptual cognition a nanosecond later.

In accordance with this difference concerning nonconceptual andconceptual cognition, Gelugpas say that voidness can be indicated by words and concepts: voidness is what the word "voidness" is referring to. Sakyapas, Kagyupas, and Nyingmapas assert that voidness - whether self- or other-voidness - is beyond words and concepts. Their position accords with the Chittamatra explanation: words and concepts for things are artificial mentalconstructs. When you think "mother," the word or concept is not really your mother. The word is merely a token used to represent your mother. You cannot really put your mother into a word.

Use of Chittamatra Terminology

In fact, Sakyapas, Kagyupas, and Nyingmapas use a lot of Chittamatra vocabulary even in their Madhyamaka explanations, particularly in terms of highest tantra. The Gelugpas rarely ever do. When non-Gelugpas use Chittamatra technical terms in highest tantra Madhyamaka explanations, however, they define them differently from when they use them in strictly Chittamatra sutra contexts. For example, alayavijnana(foundation awareness) is one of the eight types of limited awareness in the sutra Chittamatra system. In highest tantra Madhyamaka contexts, foundation awareness is a synonym for the clear-light mind that continues even into Buddhahood.

Summary

These are some of the major areas of difference concerning profound philosophical and meditation points. We could go into tremendous detail about these points, but I think it is very important never to lose sight of the fact that about eighty percent or more of the features of the Tibetan schools are the same. The differences among the schools are mostly due to how they define technical terms, which point of view they explain from, and what meditation approach they use to gain a clear-light awareness of voidness.

Preliminary Practices

Further, the general training practitioners receive in each of the traditions is the same. Merely the styles of some of the practices are different. For example, most Kagyupas, Nyingmapas, and Sakyapas complete the full set of preliminaries for tantra practice (the hundred thousand repetitions of prostrations, and so on) as one big event early in the training, often as a separate retreat. Gelugpas typically fit them one at a time into their schedules, usually after they have completed their basic studies. Practitioners of all traditions, however, repeat the full set of preliminaries at the start of a three-year retreat.

Three-Year Retreats

In a three-year retreat, Kagyupas, Nyingmapas, and Sakyapas typically train in a number of sutra meditation practices and then in the basic ritual practices of the main Buddha-figures of their lineages, devoting several months successively for each practice. They also learn to play the ceremonial musical instruments and to make sculpted torma offerings. Gelugpas gain the same basic meditation and ritual training by fitting each practice one at a time into their schedules, as they do with the preliminaries. The Gelug three-year retreat focuses on the intensive practice of just one Buddha-figure. Non-Gelugpas normally devote three or more years in retreat to one tantra practice only in their second or third three-year retreats, not in the initial one.

Participation in the full monastic ritual practice of any Buddha-figure requires completion of a several-month retreat entailing repetition of several mantras hundreds of thousands of times. One cannot perform a self-initiation without having completed this practice. Whether Gelugpas fulfill this requirement by doing a several-month retreat on its own or non-Gelugpas do it as part of a three-year retreat, most monastics in all the traditions complete such retreats. Only the more advanced practitioners of each tradition, however, do intensive three-year retreats focused on only one Buddha-figure.

Conclusion

It is very important to maintain a nonsectarian point of view with regard to the five Tibetan traditions of Buddhism and Bon. As His Holiness the Dalai Lama always stresses, these different traditions share the same ultimate aim: they all teach methods for achieving enlightenment to benefit others as much as is possible. Each tradition is equally effective in helping its practitioners reach this goal and thus they fit together harmoniously, even if not in a simple manner. In making even an introductory comparative study of the five traditions, we learn toappreciate the unique strong points of our own tradition and to see that each tradition has its own outstanding features. If we wish to become Buddhas and to benefit everyone, we need eventually to learn the entire spectrum of Buddhist traditions and how they all fit together so that we are able to teach people of different inclinations and capacities. Otherwise, we risk the danger of "abandoning the Dharma," which means discrediting an authentic teaching of Buddha, thereby disabling ourselves from being able to benefit those whom Buddha saw that the teaching suits.

It is important eventually to follow only one lineage in ourpersonal practice. No one can reach the top of a building by trying to climb five different staircases simultaneously. Nevertheless, if our capacities allow, then studying the five traditions helps us to learn the strong points of each. This, in turn, may help us to gainclarity about these points in our own traditions when they receive less elaborate treatment there. This is what His Holiness the Dalai Lama and all the great masters always emphasize.

It is also very important to see that for anything that we do - be it in the spiritual or the material sphere - there are perhaps ten, twenty, or thirty different ways of doing the exact same thing. This helps us to avoid attachment to the way in which we are doing something. We are able to see the essence more clearly, rather than becoming caught up in "This is the correct way of doing it, because it is my correct way of doing it!"

No comments:

Post a Comment